Early last November we received enough snow to make it tough getting to deer camp. Despite what the calender said, it was the start of winter. Now, nearly six months later there is still knee-deep snow in the woods around my house. I generally enjoy winter and it's activities but c'mon, enough is enough. Cabin fever sets in after a while and by now it develops into a full blown case of the shack nasties. It's snowing again today, but much of the country is getting hit worse so maybe we are lucky. I have friends that pack it up for warmer climes to spend their winters. I recently talked to a few who returned from months laying around in sunny Costa Rica. They regret their early return but nobody believed winter would hang on this long. The rest of us just stayed here and toughed it out cutting firewood, reading, and listening to blues music.

I just finished re-reading Burton Spiller's Fishin' Around and I again admire the lengths folks went to satisfy the angling urge. Born in 1886, Burt lived in New Hampshire and when he wasn't busy raising prized gladiolus flowers and hunting grouse, he made excursions into Quebec and Nova Scotia fishing for brook trout, lake trout, and land-locked salmon. When he went fishing it wasn't the often “See ya later, Honey. I'll be back Sunday night.”

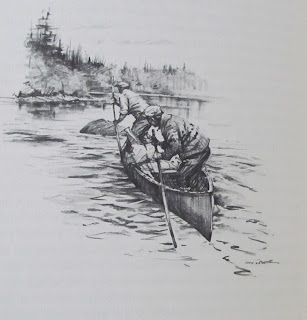

He tells of traveling rough roads

taking seven hours to cover 50 miles getting to a rustic lakeside camp

to meet his Montagnais guides, then loading gear into big canoes and paddling miles into the bush searching for sport. Nowadays those trips

are made in floatplanes, flying out for the angling and back

for dinner and soft mattress at the lodge each evening. But back then they thought

nothing of carrying hundred pound sacks of flour, pails of lard,

canned goods, slabs of bacon, coffee and tea over day-long portages

and enjoying a smoke of black tobacco as a reward. Some dried moose

meat was often tucked in but fish were a main staple. Their camps

consisted of an oiled canvas tent, two Hudson Bay blankets per

person, and beds made of spruce boughs. For them, a week in the bush

was just getting started.

Burt didn't write about how to catch

fish. Or about rated rods and lines. He mentions his rod only as a

four ounce bamboo, and his line was greased silk. He did have a fly

he liked but doesn't say much about it. His tales are about the life:

the hazards and skills of poling a canoe up through rapids, the

earned ache of muscles after a mile portage on a faint trail, the

futile effort to keep pace with the canoe-laden guide, the long battle

against a big salmon only to lose it at the net, the sizzle of trout

in a cast iron skillet. He writes about the wildlife, the people, and

the country along the way. The pencil illustrations by Milton Weiler

are first rate.

I don't know much about literature

but I know I like this, and while reading I couldn't help the desire

to get out there. I can't match Burton's trips, or ever come close,

but I did plan a date in the Boundary Waters Wilderness for June.